Metadata

aliases: []

shorthands: {}

created: 2021-11-26 18:41:40

modified: 2022-04-20 19:35:42

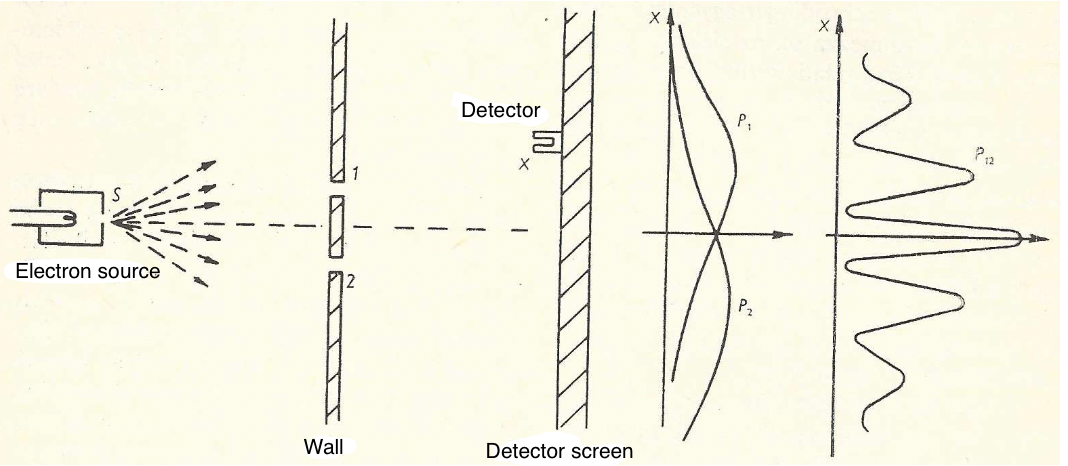

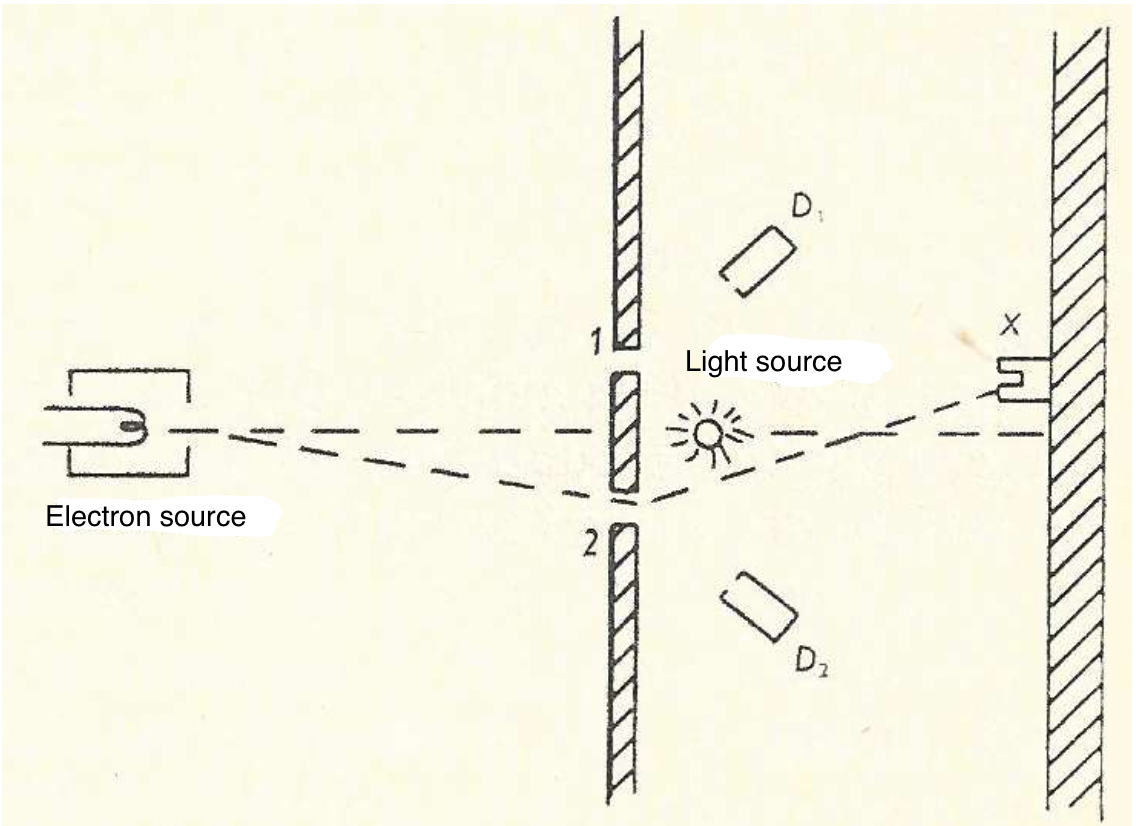

The double-slit experiment is one of the most widely known experiment regarding quantum mechanics. It was first conducted by Claus Jönsson German physicist in 1960 and published in 1961.

In this experiment, electrons are shot at a wall with two slits on it. Behind the wall, there is a detector screen, which can tell us where an electron ended up after passing through one of the slits.

Interestingly, on the detector screen, we get an interference pattern on the spatial distribution of incoming electrons, even when they are shot one at a time. This proves that they act like waves and can interfere with themselves. (See wave function.)

Starting state: the electron starts from the

End state: The electron is detected in the

Event: The starting state and the end state is specified. The event can occur in two mutually exclusive manners: it can either pass through hole 1 or hole 2.

Let's consider the second postulate and let the probability amplitudes of the different routes be waves:

Where

Then in case of

And with this the probability:

Where

With this modeling, when

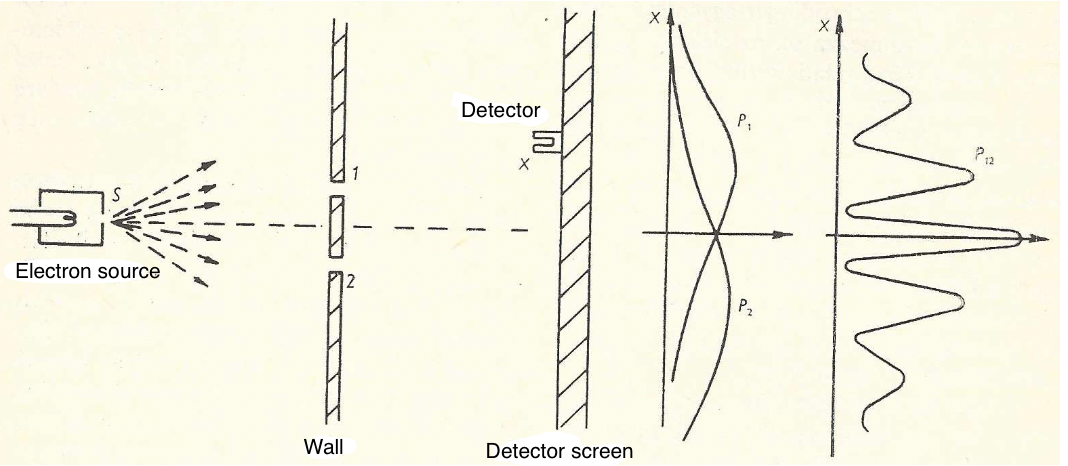

Let's look at the third postulate. By having detectors near both slits, we can know which one the particle passed through. Let's call them

In this case, the end state of the electron is not only described by the

With these, the probability amplitude of the electron getting to point

And the probability amplitude of the electron reaching

Here we used the second postulate and the fact that the probability amplitudes of conditional events get multiplied.

If we manage to tweak the experiment (for example by lowering the wavelength of the light) in a way so that for the electron passing through slit 1, there is a much larger probability for the photon to be detected in

Then the probability of detecting the photon in

And the probability of detecting it in

The complete probability of the electron ending up in point

Here we used that we considered two independent events, so we have to sum their probabilities, not sum their probability amplitudes like when the events are mutually exclusive:

The properties described above are related to the collapse of the wave function.